Doughnut Economics

This is the first post in an ongoing series that we hope will share some of the foundations of the approach Elevated Denver is pursuing in our work. We’ve found these topics to be mind-bending and they offer new opportunities to organize our combined efforts in better ways, learning from each other and focusing on the things that matter most, together. This series is not absolute or final. We are all still learning new important things all the time, and as we do, we will add to this series. But for now, enjoy part 1 on Doughnut Economics.

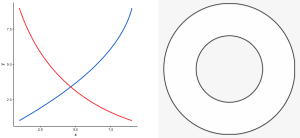

Can a picture change the world?

If we suggested that these pictures hold the power to create global change, would you think we are nuts? The one on the left is a simple supply and demand curve. The one that has been taught in economics classes around the world for generations. The one on the right is a radical new concept with the potential to upend economic theory and maybe, just maybe, help to create a socially and environmentally sustainable world.

The Basics – what is it and what can it do:

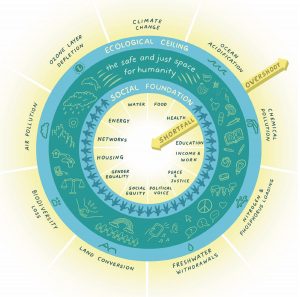

The Doughnut (above right) is the visual concept from Kate Raworth who first drew it in 2011 while working with Oxfam (inspired by cutting-edge earth-system science). She and the community that has emerged since, have continued to revise, remake, and reiterate the concept to incorporate new metrics and new ways of using and illustrating the model. With that, the model, and Kate’s larger work, is more than just a picture.

It’s really an approach. A way of understanding economies and how they can be designed so that all people can live healthy and fulfilling lives. It’s a way of viewing one’s role in their neighborhood, their city, or in the world at large and seeing one’s impact on those ecosystems based on their day-to-day actions. Ultimately, it’s a way of seeing and being in the world that honors all of the value adding activities that support communities and ecosystems.

Doughnut economics, in Kate’s words, “raises four key implications for the pursuit of human wellbeing…. First, it highlights the dependence of human wellbeing on planetary health. The best chance of enabling a life of dignity and opportunity…depends on sustaining…a stable climate, clean air, a protective ozone layer, thriving biodiversity, and healthy oceans. Second, the concurrent extent of social shortfall and ecological overshoot reflects deep inequalities—of income and wealth, of exposure to risk, of gender and race, and of political power—both within and between countries.

The Doughnut helps to focus attention on addressing such inequalities when both theorising and pursuing human wellbeing. Third, the Doughnut implies the need for a deep renewal of economic theory and policy making so that the continued widespread political prioritisation of gross domestic product growth is replaced by an economic vision that seeks to transform economies, from local to global, so that they become regenerative and distributive by design, and thus help to bring humanity into the Doughnut.

Last, the Doughnut might act as a 21st century compass, but the greater task is to create an effective map of the terrain ahead. 9“

What’s in it

The Outer circle represents the ecological ceiling, those earth systems that are essential for life on this planet to live as it has for thousands of years. The systems defined on the Doughnut are based on the work of Johan Rockstrom and Will Steffen and other international earth-system scientists. They identify 9 necessary systems—like freshwater withdrawals and biodiversity loss—that together support earth’s ability to maintain stable environments for human life to thrive.

Doughnut Diagram, designed by Natalie Horberg

Overshoot are those indicators that exceed the outer boundary. To have one or two overshoots is certainly not great, but the bigger problem lies in the positive feedback loops these systems have on one another. So as one system goes beyond it’s ecological ceiling, it puts pressure on other interrelated systems forcing them to also move towards overshoot. This is why many have been sounding the alarm for many years—earth-systems don’t change in a linear fashion, and if we don’t do something now, our catastrophe will happen faster than we expect.

The Inner circle represents society’s social foundation, identified as 12 basics of life that all people should have access. These include sufficient, healthy food; clean water, housing, justice, to name a few. Like the ecological systems that impact one another in both positive and negative ways, these social systems also reinforce each other both for benefit or not. Fortunately, attention to these systems has grown dramatically over the past five decades and more efforts are being made to ensure these foundational components are part of community strategies.

In an interview, Kate mentions that her insight to the inner circle stemmed from her consideration of moving all of the environmental systems to zero (the opposite of overshoot) and she realized that we would all be dead if that happened. It occurred to her that there must also be an inner boundary, one that recognizes human use of natural resources but constrained by impacts on human thriving. The space between the outer and inner boundaries, besides looking like a doughnut, represented the “sweet spot” for human flourishing.

Why Use it

For our work, there are three distinctions we like to highlight regarding the effectiveness of this model as a compass and why we like it. First, the Doughnut’s primary communication pathway is through a picture. So communication becomes more intuitive, collaboration can become more focused, aligned, and action-oriented. New metaphors can lead to new ways of being and seeing the world—leading to systems that are more fit for generational thriving.

“Never underestimate the power of such images: what we draw determines what we can and cannot see, what we notice and what we ignore, and so shapes all that follows.”.

The second distinction is near and dear to us—the mindset and worldview shift that the model helps to cultivate. It illustrates the degree to which different human and ecological systems are thriving or not, and by working with it, forces one to see the interconnectedness of each of these systems—both human and environment—and how a holistic approach is the only plausible way to find long-term solutions and eliminate externalities.

Additionally, because it allows us to hone in on specific issues, it helps us stay focused on the task at hand, one step at a time, becoming a form of mindfulness practice. Over time, one begins to focus on just planting the seeds—less thinking about what will flower, and more about tending to the conditions for that which will flower.

This long-term tending—intentionally caring for something over time—is a necessary ingredient to our collective mindset and stance if we are to align expectations and take the necessary approaches to do design holding a more comprehensive framework.

At essence, we see thriving as a process…as desired conditions shift, the behaviors and ways of living need to shift to remain in that sweet spot/Goldilocks zone. The Doughnut helps us navigate those changing conditions.

The third distinction is the communities around the world using this model in a multitude of ways, and their willingness to share and mentor others along the way. The community of practice is one of the best I have come across over the past two decades in terms of diversity of content and engagement. None of us can do this on our own. Knowing we have a supportive community of practitioners provides us with peace of mind and allows us to focus forward to co-design an Elevated Denver.

In summary, we like it because it paints a simple picture that lets all engaged focus in resonance. The process of using the model and taking action elicits a mindset shift to a longer-term, more systemic view where interconnectedness and the relationships between people, organizations, neighborhoods and the larger ecosystems in which they reside is what leads the action steps. And there is already a community of support with case studies occurring all over the world–giving us the necessary resources, collaborators, and guides to do what we want to do, and do it well. Lastly, we like that the content can be specified by the community itself. If we in Denver want to narrow in on particular realms like food, climate, housing and mental health, then those can be the pictures/ metrics used as anchors to track what’s important to us.

If you would like to go deeper into Donut Economics, please take as many minutes as you are willing to invest considering the content or this video:

If you want more videos, consider following these links:

Kate Raworth on Growth(3:26) – this doesn’t specifically talk about the Doughnut but her view on “growth” is so relevant to the mindset required (imo).

How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy – BBC REEL(BBC Reel with Kate) (6:30) – i like this one for the “short video”)

Downscaling the Doughnut to the City (11:20)

And of course, if you really want to learn this, a great place to start is reading the book:

Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut Economics Seven Ways to think like a 21st Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

We pulled Illustrations and quotes from these places, which we’d also recommend visiting:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/ – Main Page

https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools-and-stories – Tools and Stories

Link to original source of Kate Quote “raises key implications…”: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(17)30028-1/fulltext – (see Supplementary Information for an in-depth exploration of the social indicators and boundaries selected for use in Doughnut v2.0)

We look forward to building on this discussion with you. Stay tuned for the next installment which features the City Portrait, another tool that helps us see a community of interest—neighborhood, city, or nation—from the multitude of perspectives that each community holds.