Blog

ALL POSTS

A Veteran’s Perspective

A Veteran’s Perspective | By Joseph Ellis, Program Administrator Outreach Court & Forensic Peer Navigator Supervisor, Denver County Court

From Serving in the Army to Houselessness & Addiction

I spent so many nights in strange places during my time in the Army. I spent nights sleeping on the ground, on top of fuel tankers, in an ambulance, in makeshift hammocks, and sometimes just crunched up in a seat in a Humvee. As uncomfortable as it was, I saw it as part of the job. I think that made not having a proper place to sleep during my addiction struggles not only tolerable but I actually saw myself as being resilient and resourceful for being able to survive that way.

In my ten hard years of substance use I had burned so many bridges with family members and friends. My priorities were so messed up that I spent my time and what little resources I had on drinking or using and where I laid my head would just work itself out. I was fortunate that I had family and friends who cared more about where I was than I did myself. For over 8 years of my use, I had no place of my own. I slept in cars, stayed on couches, lived with others, palettes on the floor, and finally ended up on a mattress in my father’s basement cursing that the sun had come up. During those years, I genuinely believed that I could survive whatever may come at me. I ignored the loving advice of friends and family telling myself, “That’s not what’s going to happen to me… I’ll show them”. I believed I could find a way to live a normal life and use substances and I tried time and time again, only to watch it crumble because of my addiction in every situation. I burned more bridges and did more damage. I’ll never forget the moment I laid there on that mattress and told myself I couldn’t do it anymore. I was either going to get busy with death or get busy with life. I knew I couldn’t do that to my children and family, so I chose to continue to fight. To fight for what I wanted my life to look like.

Treatment & Support

I was always told in treatment programs and support groups that I had to surrender and I couldn’t conceive of what that looked like. I had no idea how to surrender. I chose to do a two-year program in a therapeutic community because it was the hardest free program that I could find and had tried most all other modalities of treatment and failed at them. My life changed from the moment I made that choice to go on. My father, whom I had hurt and failed so many times before, asked me to promise him that I would give everything I had to this program. He said, “I know in my heart if you do that, you will succeed”. There have been times of struggle in which that promise was the only thing that kept me focused.

Veterans are incredibly resilient, resourceful, and at home with adversity. Special Warfare Command spends millions of dollars studying how to find these attributes in people, recruit them, and hone them into the greatest forces on the face of the earth. Those attributes are praised and highly valued. Oxford defines “resilience” as the capacity to withstand or to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness. Veterans are taught to have pride in everything and told they are the ones keeping our world free and safe. When you’re serving, it’s an ideal that you live by and a value that everything gets run through. You put others before yourself in everything. You go hungry, deprive yourself of sleep, get to the medic after everyone else has been cared for–making sure that every member of your team gets fed, patched up, and rested before yourself. You’re encouraged and praised for being able to “suck it up” and told that’s what makes a strong soldier. All these notions of self-sacrifice are drilled into you and may pay dividends in a war zone and especially so outside the wire. But what happens to those notions when you’re not in combat or in the field? Those same values and attributes don’t just disappear. They work against us and we repeat the motto “suck it up” in our heads. “You can handle this.” “You’ve got this.” When you’re using substances to cope with the situations in your life, these platitudes are dangerous and could very well kill you. Sometimes when you’re struggling to survive your pride is all you have to lean on. How are you supposed to surrender to the fact that you can’t manage your life when you’ve been trained to fight until your last breath and never concede defeat?

Through the grip of addiction and mental health crisis we become different people all together. We start sacrificing our values and doing things we never would’ve done, in our right mind. We develop shame and guilt. We carry moral injuries and terrible experiences. We wonder if mentioning it to someone else will be perceived as weakness or failure and we stay trapped in it, not knowing how else to cope with it. No one wakes up one day and says, “I want to become addicted to substances, ignore my wellness, and systematically hand my life over to them until the only thing I know how to do is use substances to escape the pain of living”. People take different paths to it but neglecting our wellness and using substances to cope only ends up in death. Whether physical, spiritual, or emotional death, it’s no way to go through life. Everyday becomes survival. It’s painful to think that there are people right now, today, that only know one way to make it through another day by using substances to salve their pain. For many years, I used substances not for euphoria but because I didn’t want to deal with being sick and in physical and emotional pain and saw no other way. My pride wouldn’t let me see that there were so many more healthy solutions being offered that I could try.

Recovery & Giving Back

I’ve been in long term recovery from substance use and mental health issues since March 21, 2013. I’m very proud that I’ve been in recovery longer than I was in my active addiction now. The first time I let someone help me, I realized what a double-edged sword pride can be. It felt strange and somehow weak but at the same time SO much weight was lifted off my shoulders. From then on asking for help and surrender (in some capacities) made more sense than trying to fight alone. I didn’t have to have all the answers. I could accept a hand up. Someone was willing to make sure all of my basic needs were met and I could focus on rebuilding my life. Treatment was one of the most difficult things I’d ever done in my life… but worth every second of it and more. I got to crawl, walk, and then run back into a life of recovery.

Today I have the privilege of helping other people try to find meaningful change. I get to work in the criminal justice setting with treatment courts and specialty programs that encourage treatment instead of incarceration. I’m blessed beyond measure and never could’ve imagined my life could be as good as it is. Life in recovery is not without its challenges and frustrations. I get to help others find the power that they had the whole time and didn’t know how to get back in touch with it. It all began with working on my pride, asking for help, and trusting in something outside of myself. I don’t like thinking about my past. But it is incredibly important to help me remain grateful in my life today. I choose to believe that by sharing my story I may be able to help at least one person with it and that in itself is plenty of reason to share it.I have devoted my life to trying to make a difference for others who struggle with the same things I did. Today, I’m a certified addiction counselor and I counsel folks in early recovery who are in treatment, and I get to teach psycho-educational classes. I’ve also worked to become a Colorado Certified Peer & Family Specialist and a Recovery Coach Professional Facilitator (RCPF) and my vocation is training others that want to help folks going through what we did. That’s part of the beauty of recovery. It’s a shared gift that gets stronger by giving it away. I’ve been privileged to help many veterans find services, get connected to benefits, housing, treatment, and build strong support systems that offer the camaraderie and belief in community that I had when serving. If you are someone blessed enough to have found recovery and that meaningful change, you can continue to pay it forward and help the next person who is struggling. There are so many people and organizations out there that can help you with your challenges. Regardless of your service status and honestly regardless of your veteran status. They want to help you as a person realize the life that you deserve to live. Please put away the pride (for a bit) and ask for help. I promise you that you will find more help than you know what to do with.

Resources

Veterans have many resources available to them both through the VA and outside of it that can help. The VA is not the only choice you have. There are so many non-profit and community organizations and programs through the city specifically for vets. No matter your service. There is the Colorado Coalition for the homeless and their Homeless Veteran Reintegration Program, (HVRP), and Rocky Mountain Human Services has a program called “Homes for all Veterans” that will help you find a place and pay first and last month’s rent for you so that you can have a stable place to live. The VA offers substance use help, mental health services, and other supportive services that can help make life better for those struggling with just that basic needs of life. But there seems to be a big disconnect between those services and veterans who need them. A lot of vets make the mistake of assuming that they aren’t eligible for services for whatever reason and may not even ask. Some have no idea the services exist and are able to be used. THIS is where that pride comes in again. Instead of making assumptions about availability or eligibility, just check it out. Take a positive step and look into them. It may take some work but is worth finding out what help and hope exists for you.

Don’t stop with the VA. Check out all the Veteran Non-Profits that are out there and how they may be able to help you. In my experience these organizations are just out to help other veterans with no strings attached. I’ve seen the Vietnam Veterans of America help to pay for a veteran of recent wars CDL test. If you are struggling with substance use and/or mental health issues, reach out to WarriorNow. They are ingrained into the veteran community and can point you in the right direction based on your needs. Please reach out.

- VA homeless services: https://www.va.gov/homeless/housing.asp

- Veterans Community Resource Center

Located in: Inner City Health Center

Address: 3836 York St, Denver, CO 80205

Hours: Open ⋅ Closes 3 PM

How to give back/Help vets in need:

- Help homeless vets: https://login.builtforzero.org/about-built-for-zero/

- Become a Mentor for Veterans Struggling with substance use and mental health concerns: www.warriornow.org

- Become a Peer Mentor in Colorado Veteran Treatment Court https://www.courts.state.co.us/Administration/Custom.cfm?Unit=prbsolcrt&Page_ID=742

The Critical Need for Palliative & End-of-Life Care for the Unhoused

The Critical Need for Palliative & End-of-Life Care for the Unhoused | By Dr. Pilar Ingle

“You know, hospice care is actually hard for the housed. So, it’s like a thousand times harder for the unhoused.”

This quote comes from my dissertation project, where I interviewed 17 healthcare and social service providers around Colorado in the summer of 2022 to find out more about their experiences working with unhoused individuals with life-limiting (advanced chronic illness that limits the life expectancy of a person, such as cancer or heart failure) or terminal illness (end-stage of a life-limiting illness). The speaker of this quote, who has experience working for hospice organizations and homeless service organizations, remarked on the challenges many people with terminal illness face when considering hospice care whether they are facing housing instability or not. Can they receive hospice at home? If hospice providers are only in the home a few hours per week, who will be there the rest of the time to care for them? For someone who is unhoused, these challenges are even more complicated in the face of houselessness, competing needs, social isolation, and inequitable access to healthcare.

As a healthcare researcher who studies access to palliative and end-of-life care, I believe everyone is deserving of care and a dignified death. Palliative care and hospice are forms of integrated, medical care that focus on quality of life for people with life-limiting or terminal illness, including pain and symptom management and psychological, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. Palliative care is for anyone with a life-limiting illness from the time of diagnosis all the way through the end-of-life, whereas hospice is provided for individuals who are expected to die from their illness in six months or less. Yet, our society does a poor job of prioritizing palliative and end-of-life care.

I wrote more broadly on our culture around death and the policies that impact death and dying in the U.S. in a 2021 op-ed. These same issues (death avoidance, hospice reimbursement, rising funeral costs) deeply impact serious illness and end-of-life among our unhoused neighbors and are compounded by the structural issues that drive homelessness and the related stigma. Compared to the stably housed population, unhoused individuals have higher rates of chronic and serious illness, die at much younger ages, and are more likely to die in the hospital or in unsupportive settings, such as on the streets. Over and over again, unhoused folks have expressed fear of dying anonymously, in pain, and without dignity.

Most of the providers I interviewed for my dissertation emphasized the inhumane lack of resources available to address the health needs of our unhoused neighbors who are living with chronic or life-limiting illness across our healthcare and social service systems. There are few options for providing hospice care to unhoused folks nearing the end of their lives, and the options that exist are limited in resources. Moreover, our healthcare and housing systems are often siloed and don’t communicate with one another, which makes it difficult to create plans for care that are realistic for their unhoused clients. Many of the people I talked to highlighted the need for specialized palliative and end-of-life programs designed for the unique needs of unhoused individuals, such as street-based palliative care or social model hospice homes (non-medical homes that provide two vital things that often make it difficult for individuals to receive hospice care at home: a place to receive hospice care, and the informal, family-like care needed to support individuals around the clock).

Another related, common theme from my dissertation and in conversations I’ve had since with people invested in this issue is the issue of funding: we need the funding to invest in our unhoused neighbors, to improve our services, and to create new programs that tailor to palliative and end-of-life needs for those experiencing houselessness. We see this need for funding happening in action with Rocky Mountain Refuge. Featured in Episode 12, this innovative organization is one of a few social model hospice homes in the country dedicated to serving individuals experiencing houselessness with terminal disease, and the only one in Colorado. However, they’ve struggled with funding issues due to the lack of investment in end-of-life care, particularly for people who are unhoused.

It’s important to consider that this issue is more than ensuring that everyone has access to palliative and hospice care when they have a life-limiting illness. We must also address the factors and policies that cause or hasten the deaths of our unhoused neighbors. For example, a recent study led by Denver physician Dr. Joshua Barocas found that continuous forced displacements, or encampment “sweeps”, contribute to decreased life-expectancy of those experiencing houselessness. We must confront the stigma that leads to disparities in care—including unhoused individuals being less likely to receive life-saving treatment than stably housed individuals when presenting to the hospital with a heart attack.

The bottom line: it’s going to be difficult to create meaningful and accessible solutions to palliative and end-of-life care for our unhoused neighbors without also addressing the structural factors that create and maintain poverty and homelessness. As the Elevated Denver podcast has highlighted time and time again, these issues are interconnected. And in the meantime, we urgently need better palliative and end-of-life care options, like Rocky Mountain Refuge.

To donate to Rocky Mountain Refuge: https://rockymountainrefuge.org/donate

To learn more about social model hospice homes: https://www.omegahomenetwork.org

Denver Medical Examiner’s dashboard on Fatalities Among People Experiencing Homelessness: https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Public-Health-Environment/Medical-Examiner/Medical-Examiner-Data#section-6

B-Konnected: A Keystone Program to Keep People Housed

B-Konnected: Keeping People in Housing | By Brittany Katalenas

As the Founder and CEO of B-Konnected and Konnected Technologies, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing a transformation in the realm of affordable housing and community well-being. Our Tenant Success Tool & Measurement program has become a catalyst for change, and I’d like to share some of the key insights and exciting discoveries we’ve made along the way.

1) Housing Stability Gap: We found a lack of comprehensive services for tenant households in the Denver Metro Area, leaving many vulnerable. For example, some families receiving ERAP funds also lacked promised case-management services. We’re committed to bridging these gaps.

2) Data-Driven Eviction Prevention and Support: Both tenants and landlords need robust support systems to prevent evictions and improve residents’ Social Determinants of Health: proof that residents are living happy fulfilling lives. We’ve developed 60+ indicators of housing stability, successfully stabilizing 9 out of 10 referred residents.

3) Community Building: Our approach emphasizes long-term solutions and collaboration between public and private sectors. We advocate to address housing issues at their core and connect fragmented systems. We work closely with landlords to ensure that they have the resources and support needed to maintain housing quality standards and create healthier communities.

B-Konnected’s holistic approach to housing stability is a beacon of hope in the ongoing engagement against homelessness and housing insecurity. Our commitment to collaboration with both households and landlords, data-driven problem solving, and proactive support is reshaping the landscape of affordable housing, one community at a time. Together, we can create communities, not just housing, and empower residents to thrive.

For additional information about B-Konnected, please visit bkonnected.org.

The Denver Basic Income Project

The Denver Basic Income Project | By Gwen Battis

“When you build a house, you have to start with the foundation. You can’t start with the walls and then bring in a

foundation. So that’s what the DBIP program has done for me—it’s giving me a strong, sturdy

foundation to be successful and to be productive.” (DBIP Participant)

The Denver Basic Income Project (DBIP) is studying the impact of providing direct cash assistance to unhoused people living in Denver. A direct cash transfer system is a way to reduce wealth inequality and improve human thriving. Our approach and decision-making is centered by the input from those with lived experience, those on the frontlines, and those currently experiencing homelessness. With more than 32,000 individuals experiencing homelessness in Denver Metro alone, the learnings from this program will be invaluable in informing the future strategies and policies that serve this community.

DBIP conducted two pilots in August 2021 and July 2022 to test the program design and assumptions. Using the learnings from those studies, we launched the full program in November 2022 and participants began receiving payments thereafter.

DBIP is distributing cash payments to 807 individuals/families experiencing homelessness with dignity and speed, and with research methods implemented to analyze the project’s impact. We want to learn and identify which approach has the greatest impact including acquiring stable housing, overall well-being, and economic security.

Participants were placed randomly into one of three groups:

- Group A participants will receive 12 monthly cash payments of $1,000 for a total of $12,000 over 12 months.

- Group B participants received an initial direct cash payment of $6,500 and will receive 11 monthly payments of $500 for a total of $12,000 over 12 months.

- Group C participants will receive 12 monthly cash payments of $50 for a total of $600 over 12 months.

In addition to the 807 individuals enrolled in the main program, 39 individuals enrolled in the earlier pilot cohorts also received direct cash assistance.

While participation in the project’s research component is not mandatory, nearly 93% of program participants opted to join the study. This exceptionally high opt-in rate is an initial indication that the trust placed in participants to make this choice and to decide how to use their cash leads to reciprocal trust and more opportunity for positive engagement. The research activities include surveys every six months and short bi-weekly text surveys that will ask about health and well-being, housing stability, and financial well-being. Participants are also invited to complete interviews to share their experience with DBIP.

The Denver Basic Income Project’s participant pool is designed to mirror the demographics of those that experience homelessness in Denver and reflects the project’s mission of having an equity-centered approach to outreach and selection.

Of the 807 participants,

- 67.3% identify as people of color, with the majority identifying as Black (25.77%) and Latinx (23.3%), followed by multi-racial (7.81%), American Indian/Alaska Native (4.71%).

- Nearly half of the cohort identify as a woman, non-binary, transgender, or gender non-conforming individual (49.94%).

- Nearly a quarter (22.6%) identify as a family household, with at least one dependent under 18.

- Nearly half of the cohort have some type of disability (49.3%).

The participant demographics allow the Denver Basic Income Project findings to be generalizable to inform policy and programming for the unhoused community in Denver, and capture how other forms of social marginalization intersect with experiences of homelessness.

The Denver Basic Income Project has gained national attention and is being watched by other cities across the United States as a potential model for addressing homelessness and economic inequality. The findings of the Denver Basic Income Project are likely to inform and shape policy decisions made by the new leadership in Denver, particularly regarding issues of homelessness and economic justice. Cash is increasingly seen as the gold standard by which all social impact programs should be evaluated, as it provides people with the autonomy to make decisions that are best suited to their individual needs and circumstances.

For additional information about Denver Basic Income Project, please visit denverbasicincomeproject.org and direct media inquiries to abby@allinstrategic.com.

Gwen Battis is the Program Manager of the Denver Basic Income Project.

Attainable Homeownership: The Land Trust Model

Attainable Homeownership in Colorado | By Stefka Fanchi

At Elevation Community Land Trust, we believe that when people have equitable access to opportunity through affordable homeownership, communities, economies, and families thrive. That equitable opportunity is not being provided by the market. In many ways, it feels like this is a new obstacle – that we are fighting for something our parents had, but that is now out of reach. But access to homeownership has never been equitable.

The community land trust model came out of the Civil Rights Movement, when a group of black sharecroppers were evicted from their land and livelihood in retaliation for daring to register to vote. They collectively purchased a tract of land in rural Georgia, which they intended to farm cooperatively. Soon they realized that it was necessary to balance their collective prosperity with the needs of individual farmers and their families. This became New Communities, the first community land trust.

In a community land trust, individuals are able to purchase a home at a reduced, affordable price that does not include the value of the land. The land beneath the home continues to be owned collectively, or by a nonprofit, and is held in trust so that it can only ever be used for affordable homeownership. The homeowner enters into a 99-year, renewable land lease that provides them all the rights and responsibilities for the land. That document ensures owner-occupancy, and permanent affordability through a restricted resale price. Through this model, lower income households can achieve homeownership, build wealth through equity and appreciation, and pass that same opportunity on to another family.

At a time when home prices have increased exponentially, and so many of what were once starter homes are now in investor hands as rentals, community land trusts are more important and more relevant than ever. We are at a critical and precarious time in Denver, in Colorado, and across the nation. As housing becomes a scarce and precious resource, more of our neighbors are falling into homelessness, and those lucky enough to enjoy a stable renting situation have all but given up on the idea of owning a home. We must reframe housing as a human right, and create an attainable pathway for people to become housed, stay housed, and use that stable platform to thrive. Without the option for affordable ownership, we will thrust ourselves further into economic inequality.

Homeownership is the surest route to fiscal stability and intergenerational wealth, but its benefits are not purely financial. Studies have proven that homeowners are more likely to vote, to volunteer in their communities, to engage in their children’s education, and to pursue their own education and growth. They experience less stress, are more likely to have health insurance, and have shorter commutes. At the root, homeownership creates more choices for families. Community land trusts are a tool to control and create those choices, acting as a buttress against outside forces like gentrification and appreciation that displace long-time residents.

Elevation Community Land Trust uses a three-pronged strategy to build a pathway into ownership for those who have been locked out. First, we partner with local governments to identify areas at risk of displacement, and purchase homes in those neighborhoods. Those homes are then rehabilitated, subsidized, and made affordable and available to residents making less than 80% of the area median income. This takes those properties out of the hands of investors and places it in the hands of communities. Second, we construct new homes in desirable areas to increase the stock of homes and ensure they are permanently affordable. Finally, through our new Doors to Opportunity program, we double down on family choice by coming alongside buyers who have found their dream home on the market, buying it with them so that it can be affordable now and for generations.

Since our first home was sold at the end of 2019, Elevation has scaled its portfolio to more than 500 homes in 13 communities, and has 600 additional homes in its pipeline. Over the next five years it is our goal to build that portfolio to 1500 – a 75% increase in the number of permanently affordable homes in Colorado today. We cannot accomplish this important benchmark without partnerships with the State, local communities, charitable foundations, anchor institutions, and large employers providing funding to fill the substantial gap between what it costs to build a home and what is affordable to a lower income household. Elevation also partners with private developers and banks to accomplish our work. We are especially committed to working with developers and contractors led by women and people of color who encounter barriers to entry in the industry.

As much as we are a growing city, Denver is small. We all know someone – love someone – who has struggled with housing instability or has been frustrated in their attempts to become a homeowner. My sister and her family were forced to move out of state for this reason, and I mourn not having them here just as I sympathize with my friend who cannot move despite his growing family. So many Coloradoans have abandoned their hopes and dreams of homeownership. The interest rate environment is doing even more to quash those dreams. The good news is that Elevation and five other community land trusts are working in our state to restore balance to our broken housing system. If you or someone you know is working toward the stability of homeownership, learn more and apply today at www.elevationclt.org, and don’t defer those dreams any longer.

Stefka Fanchi is the President & CEO of Elevation Community Land Trust in Denver Colorado.

How Can We Help Homeless Students Succeed

Helping Homeless Students Succeed | By Mindy Sandoval

I work closely with homeless college students in my role as a Peer Resource Navigator with the nonprofit Warren Village, and that has opened my eyes to the many struggles these students face in our community.

Imagine writing an essay on a smartphone with a dying battery while you’re out in public, and you’re worrying about your safety while doing so. Imagine having a physical ailment on top of trying to work and go to school while having a small child to care for. These are only a couple of examples from students that I personally met.

I also hear comments from people outside of this demographic like “They’re so lucky, I wish I was poor enough to win that kind of scholarship” or “Those students don’t deserve to get a hand out, they should go out and work.” The reality is many unhoused college students work more hours than many housed students and also accomplish just as much in their education.

But, there are not enough programs or funding available to support students who are trying to escape the trenches of homelessness and poverty.

Some existing programs also have unrealistic expectations for homeless students. For example, there are programs that require full-time enrollment which is difficult for students facing housing instability who hold multiple jobs. The programs may also require a GPA over 3.0, which is above average, to prove the student represents a good investment of those funds. Even though most of the students I met through the programs I worked and volunteered in were students with high GPA’s, it’s not the typical scenario for many homeless students.

So, how can we help these students succeed? One major way needs to be housing. Most affordable or subsidized housing is held for single parents or those with disabilities, not single students who are sleeping in their car or staying with a friend. If they are out of sight, they’re out of mind, and there is no help for those we don’t see. Thinking outside of the box to create a housing system that supports homeless students would make all of the difference to students, business owners and the economy.

Another solution is to better educate students about the college system itself. So many students start out at a university because they think that an associate’s degree is less likely to support themselves and their families. Universities could provide more information about different pathways to enrollment suggest that the student take classes at a community college then transfer to a university. This approach can save a student a lot of money in the long run.

Schools should also suggest taking out loans as a last resort. School support staff are not always trained on how to propose or counsel the student on the best way to use grants and scholarships, nor do they always know what all of the educational expenses are on a tuition bill. Most homeless students I met are on Medicaid and didn’t realize the school was charging them a significant amount for school based medical support and could get that fee waived. Impoverished and homeless students who take out student loans also put themselves at risk of spending a longer amount of time in poverty by having to pay back the loans, some of which carry high interest rates.

It all goes back to the public understanding that the unhoused are not just living out on the street corner—they’re all around us. They are us.

Mindy Sandoval worked with homeless students as a member of the advisory boards for the nonprofits Hide in Plain Sight and EEqual.

Podcast Episode #6 – A Thoughtful Response

How Rights and Responsibilities Relate to Trash | By Donald Burnes

After listening to the #6 podcast on street homeless encampments and trash, I was reminded of one of my sessions in my class on homelessness. This class dealt with rights and responsibilities within the framework of homelessness.

As I talked with the class, I suggested that we consider three major groups of concerned citizens: those experiencing homelessness, especially those living on the streets, the unsheltered; the commercial, retail, and overall business sector; and the general public. I also indicated that I thought each of these three groups had both rights and responsibilities.

Let’s first look at rights, and I don’t necessarily mean legal rights, but rather general moral rights. First, for the unhoused, I asserted they had a right to a safe, secure, and hospitable place to sleep at night. For the commercial and business community including tourism, I indicated that they had a right to unfettered business activity. The general public had a right to pleasant open space, clean parks, clean streets and major thoroughfares, and safe sidewalks.

Now, let’s look at responsibilities. Those experiencing homelessness do have responsibilities, namely, to take care of bodily functions so as not to despoil public or private property, dispose of trash in acceptable ways, minimize public disturbances as much as possible. However, in order for the unhoused to carry out their responsibilities, facilities must be made available—port-a-potties, shower trucks, trash receptacles/dumpsters, medical emergency equipment available in case of physical or behavioral health emergencies, etc. Without these facilities, how are the unsheltered supposed to take care of bodily functions in a clean and sanitary manner, dispose of trash safely, take care of medical emergencies?

For the commercial and business interests, they have responsibilities too. To make sure their rights are protected, they must work to ensure the necessary facilities are available to the unsheltered. If they don’t want human urine and excrement or human bodies on their doorstep, they have a responsibility to ensure the unhoused have acceptable facilities. They also have a responsibility to the general public to create a positive community environment both for improving their own revenue and for working toward the public good. Either through creating facilities by means of their own resources or by advocating that the city provide the appropriate facilities, they must fulfill their own responsibilities.

The same is true of the general public. It is by creating political pressure on the business community and/or by urging the city to provide facilities that the public can fulfill its responsibilities. I would argue that members of the public have a significant choice to make, i.e., to focus on their own personal well-being or to be sensitive to the well-being of the entire community.

In the early part of the #6 podcast, Liane Morrison asked, “Why doesn’t the City provide trash receptacles?” Unfortunately, that excellent question is never answered. An educated guess would suggest that it would be much cheaper for the city to provide the appropriate facilities and even hire an unhoused person to monitor and oversee each encampment than it is to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to sweep the encampments regularly. Such a change in approaches would also be of tremendous benefit to those forced to live in such unhealthy environments.

Finally, I ask you to stop and think about this whole picture. In fact, all three groups—the unhoused, the business community, and the general public—all want basically the same thing, namely, to have the unsheltered off the streets. Admittedly, each of the three groups has a very different rationale behind their objective, but the basic goal is the same. Why can’t the three groups come together in true collegial collaboration and work towards achieving this single important goal? Wouldn’t that be a novel approach!!!

Don Burnes has been working in the homelessness arena for almost 40 years. He and his wife are the co-founders of the Burnes Institute for Poverty Research at the Colorado Center on Law and Policy.

Meet Akusua: Artist, Creator, and Life-Long Student

How Denver’s Lack of Affordable Housing Exacerbated a Health Crisis

While waxing philosophically with Akusua about British comedies and the poetry of Sylvia Plath, it’s easy to forget that five years ago, she lived on the streets of Denver. In the throes of a mental health crisis, and without family to rely on or access to housing, she didn’t have another option.

Today she sits on a Zoom call in her apartment. She has a therapist and access to medication. And she’s got her art. “My ability to be creative, even in the worst time of my life,” she said. “It’s kept me going.”

She’s grateful for her living situation, despite it not being perfect. Ownership has changed several times during her stay there. Though her building caters to the elderly and disabled, the elevator hasn’t worked in three months. Her apartment is on the 5th floor. She describes her neighbor as sweet elderly gentleman with heart problems. She worries about how he’s able to carry groceries up the stairs. “One thing I’ve learned is that you can be grateful for what you have, and you can be critical.”

Living in Denver on $1,000 a month isn’t possible

Akusua moved to Denver for an internship with Americorp in 2016. As a student at the University of New Mexico, she studied English, Africana, and gender studies, with an emphasis on psychology. After successfully completing an internship in Albuquerque, she was excited about moving to a new city.

“I completely underestimated just how impossible finding housing would be,” she said. “I just kept thinking, something will happen for me. For some stupid reason. And boy, did it hurt when it didn’t.”

Akusua wasn’t able to finish her internship. She was making less than $1,000 a month and spent time surfing couches. But she couldn’t find anything permanent. The last home she lived in was near the 16th Street Mall in downtown Denver. When that arrangement ended, she stayed nearby because of the close proximity to a King Soopers with a 24-hour restroom. “I was really in trouble, and I didn’t have the resources.”

Navigating life with a resurging mental illness

Her mental health was slipping, and she knew it. “When you’re not from here, and you don’t know the resources you can tap into, you just feel like you’re out in the wilderness.” She got kicked out of many places. Restaurants, even the library. “You’ve been here too long” became a message she heard, again and again.

Akusua describes the feeling of being alone. “When you’re on the streets, there’s this weird sense of detachment. Even when you are surrounded–constantly surrounded by hundreds, if not thousands of people just going about their day–it really just feels like you’re alone.”

Alone and in crisis

Akusua tried navigating the shelters on her own. Each time she visited one, she’d repeat her story. Which isn’t an easy thing to do, especially in the midst of a mental health crisis. “You have to talk to people, and they expect you to be calm. They expect you to be articulate. It’s not impossible, most of the time, with medication. But if you don’t have medication … and you’re checked out and not where you need to be mentally. Well, you’re trying to explain your situation, and you’re also trying not to scream and run down the halls.”

On her own and on the streets, she found the wherewithal to apply for Social Security, because she knew it might be a while before she was able to work again. Doing so is a source of pride for Akusua. When asked how she was able to find the motivation to complete the process, she had one word: “Childhood.”

Caregiving at a young age

Growing up, Akusua had to figure things out on her own. Her mother, a veteran, had a serious mental illness. “No adolescent should need to figure out what I had to figure out.” Yet she pulled on her childhood experience when she needed to find the motivation to ask for help. “So I’m telling myself, Okay, you’re not doing good,” she said. “I remember one particular moment. It was nighttime. And I knew that I had to walk myself to Denver Health to get into the psychiatric facility. And I knew that was going to be scary for me.”

She’d been a caretaker to her mother and watched her experience in the psychiatric wards. Now here she was, in her 30s, scared and alone and facing similar circumstances. “It was hard. But I did it.”

Overcoming fear to get help

Akusua had gotten herself to the hospital, but her journey was far from over. In many ways, it had only just begun. She needed many layers of support beyond her initial hospitalization. She received emergent treatment for her mental illness. But long-term treatment was still a concern.

So was housing.

Denver’s limited availability of affordable rentals became Akusua’s biggest hurdle. Though she had been given a case manager with the Mental Health Center of Denver (now WellPower), she hadn’t been placed yet.

Waiting for connections to come through

Without housing, she found herself navigating Denver’s less-than-ideal shelter options. Again. Unsurprisingly, she found herself needing urgent medical treatment for her mental illness. Denver Health admitted her for nine days before releasing her after dark. “It was snowing. It was cold. They don’t tell you when they’re going to release you until the day. But it’s not like I had anywhere to go.” Her caseworker met her upon release to let her know she hadn’t been able to connect her to housing. So on a snowy February night, she faced a choice: Use the little money she had to catch a bus to the shelters, knowing they’d most likely be full and she’d be turned away, or spend the night sleeping on Broadway.

Akusua chose Broadway. “It was one of those things where your last option is kind of your only option and it’s sometimes the worst option, you know?”

Finding people she could trust

“When you’ve been dealing with this for most of your life alone, it’s hard to trust. But this process required me to trust. At some point I realized I needed to let people help me, and I needed to trust that not everyone had an ulterior motive.” Learning to trust has become part of her healing process. “That’s something I’m still learning. I think a lot of me telling my story to others, and allowing my story to be in other people’s hands … even this takes a significant amount of trust.”

Creating is what’s kept her alive

Akusua loves stories. She remembers her grandmother telling her how, at a very young age, Akusua taught herself to read and write. Journaling became an outlet. Then in middle school, she discovered poetry and began modeling her work after Sylvia Plath. “It was awful,” she said. But later in college, she started working on her first manuscript of poems. She’s particularly proud of a poem she wrote about her grandmother.

“I remember it was New Year’s Eve, and I was sitting in this hideous studio apartment that had that 70s shag carpet. My grandmother had passed a decade before, and I always wanted to write something, not just for her, but to her.”

Her grandmother had spent her life cleaning houses. Akusua mused that what if, even in heaven, things are no different. What she wrote surprised her. The piece reimagined her grandmother in heaven, but it wasn’t the paradise she’d hoped for. “My grandmother was in this place that’s heavenly, but very sterile. She’s still the cleaning lady. There’s a line in the poem where I said, even in heaven, you can still find your reflection in God’s toilet.”

Akusua continues to write about her mother and grandmother, and their relationship with God. She’s got three manuscripts in progress. And she creates music. “I was always creating. I didn’t always have an audience. I didn’t always want an audience. But I was always creating. Creating has kept me alive.” Her ultimate hope in sharing her story is that it gets in the hands of people facing similar circumstances to her own. “I hope they can see themselves in my story. That they can see themselves in my survival. And they can see themselves in my ability to be resilient.”

Carie Behounek is a freelance writer based in Denver, Colorado.

Akusua is an artist and spoken word poet. Follow, connect with or hire Akusua:

Akusua Akoto | akusuaakoto@gmail.com | Facebook : Akusua Akoto | LinkedIn: Akusua A. Akoto

The Podcast has Launched!

Podcast Update: The Home Stretch

It is always an exciting time to be just weeks out from the release of a project. The past months have seen a flurry of activity as we’ve been securing final interviews, incorporating feedback from our advisors, rewriting bits of narration, and testing rough cuts of podcast episodes with friends and family. Elevated Denver is slated for its public release on April 20th and we can’t wait to get across that starting line. Don’t I mean finish line? No I don’t.

It’s a starting line because the release of the podcast is just the beginning of the work Elevated Denver seeks to do. In creating it over the past year, we have learned a ton, and we’ve come to understand the systems that create the issue of homelessness in our city in a much deeper and more nuanced way. We believe that the podcast will impact others, hopefully lots of others, in the same way. If it does, we think this can elevate our community’s ability to create effective solutions to this ultimately solvable problem. Indeed, that is exactly the work that Johnna plans to focus on beginning this summer.

The early reviews are that the podcast is powerful, insightful, moving, and make people feel a sense of community with all of their neighbors here in Denver. We can’t wait to see what you think of it. Be sure to jump on the email list to be notified when the first episodes go live.

The City Portrait

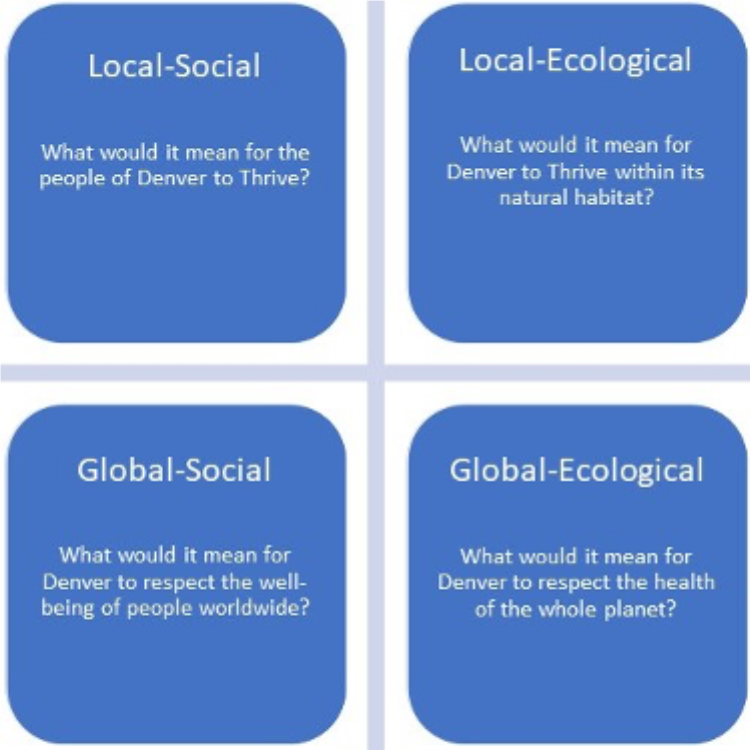

Continuing with our series highlighting some of the foundational approaches to our work, we move from Doughnut Economics to a framework designed to put the Doughnut into Action on a city scale–The City Portrait.

The first iteration of the doughnut at city scale was developed in Amsterdam with city officials and DEAL’s (Doughnut Economic Action Lab) locally based partners Circle Economy as part of the Thriving Cities Initiative. The intention for the Amsterdam City Doughnut Portrait, “building off the momentum of the city’s initiative to be completely circular by 2050…is to provide a holistic snapshot at the city’s many complex interconnections within the world it is embedded, by considering its local aspirations—to be a thriving people in a thriving place—and global responsibilities, both social and ecological.”

As we see it, the combination of using this type of thinking to inform policymaking coupled with self-organising and innovative experimentation seems to be a powerful avenue to initiate impact, across neighborhoods, simultaneously. Thus increasing the number of collaborative solutions attempted and increasing the number of opportunities for learning.

What we appreciate about the idea of the City Portrait is that it focuses on both local and global perspectives and, most importantly for us, it ties human activity to ecological impact—again both local and global. What we also like about this framework is that it is just a framework. What metrics are used and which aspects are highlighted are up to those working with it. So each iteration is a snapshot and blueprint—for your town—showing what’s here and now, what’s possible for the future, and, by working through the process, some avenues for moving conditions towards that desired future.

We’ve provided ample resources at the end of this blog for further review, but we wanted to illustrate at least a little of what building Denver’s City Portrait might entail (as we see it at this juncture). To be clear, we are not going to map all this out and then present it; this is a collaborative tool and it only works when the many perspectives and needs are incorporated into the design process.

The Four Lenses of the City Portrait Framework:

The Local-Social Lens:

The Local-Social lens asks what ‘Thriving’ means to the people of Denver and compares that vision with a snapshot of where the city is currently for those areas. The uniqueness of Denver’s Portrait will come from us—the citizens—and our collaboration to determine the set of dimensions that form our city’s social foundation. How do we want to explore and define a “basic standard of wellbeing that all city residents have a claim to achieving”?

“The 16 social dimensions used for the Doughnut were derived from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with additions of Culture, Community, and Racial and Gender Equality which were not listed in the SDGs but are generally considered important to human flourishing.”

We think these are good guideposts to consider, but we are more interested in what the inhabitants of Denver think are important and valuable and worthy of dedicated efforts to sustain and maintain over time. If we cluster these 16 dimensions, as other cities have done, on the aspiration for all citizens to be—Healthy, Connected, Enabled, and Empowered—how might we define and prioritize the attributes of each? How do we ensure each neighborhood has its own unique needs met AND fosters the health of the neighboring areas?

The Local-Ecological Lens:

The Local-Ecological lens considers the natural habitat Denver lives within, including the services provided by the habitat to the city (purifying the air, housing diverse species, storing carbon, etc); and asks how Denver might “generate these ecosystem services through its design, build, and resource use”. This view invites us to identify and adopt standards that are scientifically based in the local-ecological context of Denver, while considering the dynamics that larger ecosystem flows have on our natural habitat and our resource use.

We of course would also want to understand the natural habitats of particular neighborhoods; do the residents have what they need—clean air, water—and if not, why not? Does geography matter? How is each neighborhood connected to the ecological services provided to the city from nature and how does that impact the neighborhood’s ecological health?

The Global-Social Lens:

The Global-Social lens looks at the unique pattern of connections Denver has with other parts of the world. These connections have formed over time and are “shaped by factors such as location, history, commerce and culture.” As a way to bring in a wider, more holistic and encompassing Portrait that incorporates global implications of city life, this dimension asks how Denver’s relationship and attitudes towards other cities and cultures impact, both positively and negatively, humans around the world.

An important aspect to this dimension is the role of governance as well as the depth of cultural diversity understanding. We see both as significant factors in how we, the people of Denver, receive and welcome others and how we are received and welcomed by others around the world.

The Global-Ecological Lens:

The Global-Ecological lens invites us to consider Denver’s consumption and resource use with the city’s fair share of a globally sustainable level of resource use. It also invites us to consider Denver’s impact on the larger ecosystems within which it resides and how do we, as residents, contribute to the health (or not) of said systems?

With that, getting exact metrics for this lens is complex; and in our opinion a bit elusive. What’s important from our vantage point, at least at this stage of the consumerism culture, is the propagation of the idea for us to ‘consider our habits’; which as a reflective practice can be a powerful way for us to create the space to make different choices and create new habits. Additionally, as with the other lenses in the framework, Denver doesn’t need to work on all the categories all at once. What are one or two global-ecological dimensions that Denver either is directly impacted by or that Denver has the resource and ingenuity to offer solutions and support? We can start there and see what emerges as we progress on those targets.

Wrapping Up

So that’s the general idea of a City Portrait for Denver. We think it serves well as a framework to generate rich conversations, integrate various perspectives, while providing a guide for moving forward. As we build collaboratives and investigate the many dimensions in each lens, talking to those living and working in the space, we will map and share as we progress. Our hope is that we will inspire people to want to join in the effort of designing the Future Denver where we can all thrive. We look forward to building the conversations with you, our neighbors, as we work to build an Elevated Denver.

References and Resources:

Creating City Portraits:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools-and-stories/14

Designing the Doughnut A Story of Five Cities:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/93

A City Portrait Canvas for Workshops:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools-and-stories/76

Downscaling the Donut at 4 levels in Brussels:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/83

Amsterdam Circular by 2050 Initiative:

https://www.amsterdam.nl/en/policy/sustainability/circular-economy/

Amsterdam Doughnut Initiative: https://doughnuteconomics.org/amsterdam-portrait.pdf

Amsterdam bet on the Doughnut, other cities are now following suit:

https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/25/amsterdam-brussels-bet-on-doughnut-economics-amid-covid-crisis.html

Amsterdam to embrace ‘doughnut’ model:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/08/amsterdam-doughnut-model-mend-post-coronavirus-economy

Amsterdam:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/1

Short video of Kate’s presser after the first Portrait workshop (1:46):

How to use the City Portrait Canvas from the Thriving Cities Initiative (9:50):

Elevated Denver Workshop: Summary & Reflections

On Friday October 29th, over 20 people participated in our workshop, virtually and in person at the Tivoli Center. It was the first time we have put the concept of Elevated Denver in front of a group of people and it was a rich conversation and provided critical input and feedback that will help shape the path forward. During the workshop, we shared an individual’s story from the podcast, and spent time digging into the story as an example of navigating Denver’s social safety net system. We dug into what is happening in our system right now, why nearly half of our community is unable to make ends meet, and what is being done around the world to solve some of these challenges. Participants came together from nonprofits around Denver, from the student community, business community, and local government. We asked everyone to enter the room as citizens of Denver and everyone stepped in and stepped up with openness and honesty. The following are some themes that emerged from the day:

- In the shared story, and in many stories, the shift into being unhoused is often outside of the individual’s control and a result of a number of factors.

- Resilience and persistence are necessary qualities for navigating the system.

- Mental illness and trauma affect many of us and those are not always being identified or attended to within the current system.

- There needs to be more compassion within the social service system and a deeper understanding of the social issues facing Denver by those in positions of wealth and privilege.

- A number of economic factors are making it more challenging to survive in Denver, including wage gaps and continually increasing housing prices.

- Inequities persist in how someone can access services, which can lead to mistrust and further exacerbate the issue of engagement.

- The system is hard to navigate, and if someone is not able to access services, they are blamed instead of the system.

Some important questions also emerged:

- How will we [Elevated Denver] bring stories to light in the podcast without exploiting the individuals?

- How can we give people who need to navigate the social system real advocates?

- How might employers play a bigger role in supporting individuals, particularly around mental health struggles?

- How do an individual’s intersecting identities impact them and their journey?

We are learning from and pondering these themes and critical questions as we move forward in giving shape to Elevated Denver and the activities to come. We hope to continue the conversations as we move forward.

Podcast Production Update

We have a bold vision for a Denver where every individual, neighborhood, and entity in the community are not only able to meet their basic needs, but are set up to thrive. Right now in Denver, prosperity abounds. There is a boom of new education and tech startups, high-level jobs, and rising home prices. Denver is a great place to live, and the growth is understandable, but there is a cost of that growth. As rent and mortgage payments rise past a critical point, so does homelessness, creating a bifurcation between those at the top of the economic scale and those at the bottom. People are drawn to Denver (or compelled to stay here) because of the mountains, great beer and coffee, yes, but also because of the vibe. It is a laid-back small city where people seem to care about the environment and about their neighbors. We want to foster that sentiment and do our part to make sure we still consider our neighbors who struggle to make ends meet.

Our first step is to foster a common understanding of where we are as a community right now, and why we are here. We are doing this through an exciting new podcast where we explore complex issues around how to achieve social and environmental sustainability from four distinct Denver perspectives: citizens, the nonprofit sector, the civic sector, and the private sector. Denver has much to be proud of, and yet like other cities, the private businesses and public institutions that make Denver great still leave too many of our neighbors behind. Many of our nonprofits and public safety-net systems mitigate symptomatic pain, but they do not solve these complex issues at the systemic level. The podcast will explore the cross-sectional root causes at play as we share stories from neighbors across the city. We aren’t just going to talk about the problem. We are going to offer innovative examples and approaches from around the country and world as well as from Denver’s own history, which we will look to for future Elevated Denver work to design solutions.

Listen to the trailer below and hop on the email list to stay tuned!

Elevated Denver Workshop & Live Podcast Recording

Elevated Denver is participating in Denver Good Business Week by hosting a unique workshop at the Tivoli Building on Friday, October 29th from 9:00AM – 12:00PM.

The workshop will present a real-life case of one of our fellow Denverites who went from being self-sufficient to homeless, and is on their journey back to self-sufficiency once again. Along the way, this person’s experience highlights various parts of how our city works, for better and worse.

Through digging into the story, we can find important opportunities for improving the systems that make up our city such that cases like this one can avoid homelessness and other outcomes that harm people and our community as a whole. Workshop participants will engage in a deep discussion about these opportunities and how to create an Elevated Denver in which all of our neighbors can meet their basic needs and find fulfillment in a way that makes it easier for future generations to meet their basic needs and find fulfillment too.

The Elevated Denver team will also share an innovative new approach that is being used to elevate several pioneering cities around the world. Can this approach help to create and Elevated Denver? Workshop attendees will be the judge.

For those who are interested in moving from discussion to action, that conversation that begins at this workshop will continue all next year in the Elevated Denver 2022 Cohort.

The workshop will be recorded live as part of the production process for the Elevated Denver Podcast, and by attending you consent to have your voice and comments included in the podcast.

Space is limited and masks are required. We look forward to meeting you there.

Elevated Denver 2022 Business Cohort

Elevated Denver seeks to make progress toward the goal of creating a thriving community by convening voices from our city to find innovative ways to improve the systems in our city. We believe this work must include government, non-profits, businesses and neighborhood leaders and in addition to our podcast, we are developing a variety of approaches to make this happen.

The first two that are ready for launch are the Workshop that is part of Denver Good Business Week, and the Elevated Denver 2022 Cohort which is going to focus on and be composed of people from the business sector in our city. For the Cohort, we are partnering with the Institute for Corporate Transformation to convene 25 people from businesses across Denver to come together in a year-long facilitated cohort to explore how their companies are already creating a thriving community in our city, and where opportunities exist for those companies to further align how they do business with creating an Elevated Denver.

The cohort will go through a cutting-edge program called the Intrapreneur Accelerator which has been developed by some of the leading corporate change agents in the world to achieve the following 5 goals:

1. To get intrapreneurs to reflect on the higher purpose of their working life and to set personal goals for bringing that higher purpose to work with them, transforming, focusing, or expanding their current role as necessary to achieve it. The work of the program is all within this context and has been reported to create the experience of much-increased meaning and fulfillment for past participants.

2. To train intrapreneurs in a specific methodology to be effective in leading change inside of their companies. The methodology was created by Leith Sharpe who teaches it all over the world including for Harvard University. Here is a taste of Leith’s training:

3. To introduce intrapreneurs to a simple, but comprehensive scorecard for the performance of a business in society. The scorecard was born in a meeting in the RiNo neighborhood of Denver and over the past several years it has been refined by and is being used as the definition for success of a global coalition of changemakers who are working to leverage the power of business to create a world that works for everyone.

4. To use that scorecard to facilitate a 360 assessment of a participant’s company by that company’s own stakeholders to identify strengths and opportunities to become a strong company while creating an Elevated Denver. The assessment tool is called the Stakeholder Score and is included at no additional charge.

5. To run a real life 6 month pilot project to drive change in their company in an area of the intrapreneur’s choosing that aligns with the higher purpose of their career.

The course is delivered through an interactive mix of reading, podcasts, videos and reflection exercises as well as sharing and collaboration on a private LinkedIn group with other Intraprenuers from around the country.

Timeline and Commitment

The 2022 Cohort will begin in December of 2021 and will conclude in January 2023. The course materials in the Intrapreneur Accelerator are on-demand and can be completed at any time convenient for the participant. The 2022 Cohort will have monthly progress milestones but will do their work independently.

The exception to this will be a monthly cohort meeting that will be scheduled during the workday at a time that is convenient for the participants in the cohort. The monthly meeting will allow members of the cohort to get to know each other and share their experience, ideas, challenges and ambitions. The Elevated Denver team will also use the cohort meetings to introduce and discuss Denver-specific issue work and learning applications as the cohort works to create an Elevated Denver together by leading change inside of their companies.

It will take cohort participants 4 hours per week on average to complete course materials, do the added work to drive change in their organizations and participate fully in Cohort activities. This is not a small time commitment, but the impact of the Elevated Denver 2022 cohort will not be small either.

Cost

The registration fee is $7,500 per person and the proceeds help to to support the ongoing work of Elevated Denver.

Interested?

If you’d like to participate in the Elevated Denver 2022 Cohort, please send an email to Johnna@ElevatedDenver.co

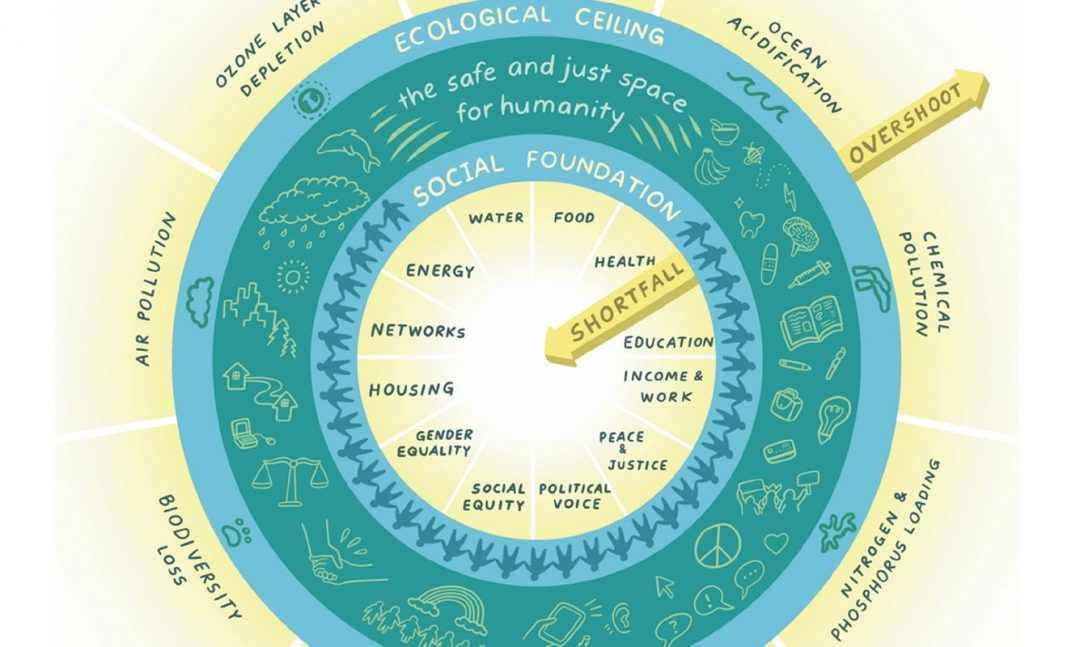

Doughnut Economics

This is the first post in an ongoing series that we hope will share some of the foundations of the approach Elevated Denver is pursuing in our work. We’ve found these topics to be mind-bending and they offer new opportunities to organize our combined efforts in better ways, learning from each other and focusing on the things that matter most, together. This series is not absolute or final. We are all still learning new important things all the time, and as we do, we will add to this series. But for now, enjoy part 1 on Doughnut Economics.

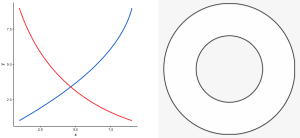

Can a picture change the world?

If we suggested that these pictures hold the power to create global change, would you think we are nuts? The one on the left is a simple supply and demand curve. The one that has been taught in economics classes around the world for generations. The one on the right is a radical new concept with the potential to upend economic theory and maybe, just maybe, help to create a socially and environmentally sustainable world.

The Basics – what is it and what can it do:

The Doughnut (above right) is the visual concept from Kate Raworth who first drew it in 2011 while working with Oxfam (inspired by cutting-edge earth-system science). She and the community that has emerged since, have continued to revise, remake, and reiterate the concept to incorporate new metrics and new ways of using and illustrating the model. With that, the model, and Kate’s larger work, is more than just a picture.

It’s really an approach. A way of understanding economies and how they can be designed so that all people can live healthy and fulfilling lives. It’s a way of viewing one’s role in their neighborhood, their city, or in the world at large and seeing one’s impact on those ecosystems based on their day-to-day actions. Ultimately, it’s a way of seeing and being in the world that honors all of the value adding activities that support communities and ecosystems.

Doughnut economics, in Kate’s words, “raises four key implications for the pursuit of human wellbeing…. First, it highlights the dependence of human wellbeing on planetary health. The best chance of enabling a life of dignity and opportunity…depends on sustaining…a stable climate, clean air, a protective ozone layer, thriving biodiversity, and healthy oceans. Second, the concurrent extent of social shortfall and ecological overshoot reflects deep inequalities—of income and wealth, of exposure to risk, of gender and race, and of political power—both within and between countries.

The Doughnut helps to focus attention on addressing such inequalities when both theorising and pursuing human wellbeing. Third, the Doughnut implies the need for a deep renewal of economic theory and policy making so that the continued widespread political prioritisation of gross domestic product growth is replaced by an economic vision that seeks to transform economies, from local to global, so that they become regenerative and distributive by design, and thus help to bring humanity into the Doughnut.

Last, the Doughnut might act as a 21st century compass, but the greater task is to create an effective map of the terrain ahead. 9“

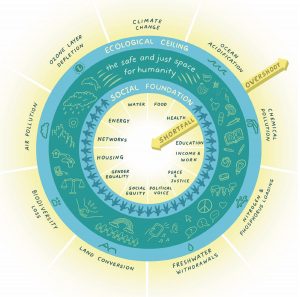

What’s in it

The Outer circle represents the ecological ceiling, those earth systems that are essential for life on this planet to live as it has for thousands of years. The systems defined on the Doughnut are based on the work of Johan Rockstrom and Will Steffen and other international earth-system scientists. They identify 9 necessary systems—like freshwater withdrawals and biodiversity loss—that together support earth’s ability to maintain stable environments for human life to thrive.

Doughnut Diagram, designed by Natalie Horberg

Overshoot are those indicators that exceed the outer boundary. To have one or two overshoots is certainly not great, but the bigger problem lies in the positive feedback loops these systems have on one another. So as one system goes beyond it’s ecological ceiling, it puts pressure on other interrelated systems forcing them to also move towards overshoot. This is why many have been sounding the alarm for many years—earth-systems don’t change in a linear fashion, and if we don’t do something now, our catastrophe will happen faster than we expect.

The Inner circle represents society’s social foundation, identified as 12 basics of life that all people should have access. These include sufficient, healthy food; clean water, housing, justice, to name a few. Like the ecological systems that impact one another in both positive and negative ways, these social systems also reinforce each other both for benefit or not. Fortunately, attention to these systems has grown dramatically over the past five decades and more efforts are being made to ensure these foundational components are part of community strategies.

In an interview, Kate mentions that her insight to the inner circle stemmed from her consideration of moving all of the environmental systems to zero (the opposite of overshoot) and she realized that we would all be dead if that happened. It occurred to her that there must also be an inner boundary, one that recognizes human use of natural resources but constrained by impacts on human thriving. The space between the outer and inner boundaries, besides looking like a doughnut, represented the “sweet spot” for human flourishing.

Why Use it

For our work, there are three distinctions we like to highlight regarding the effectiveness of this model as a compass and why we like it. First, the Doughnut’s primary communication pathway is through a picture. So communication becomes more intuitive, collaboration can become more focused, aligned, and action-oriented. New metaphors can lead to new ways of being and seeing the world—leading to systems that are more fit for generational thriving.

“Never underestimate the power of such images: what we draw determines what we can and cannot see, what we notice and what we ignore, and so shapes all that follows.”.

The second distinction is near and dear to us—the mindset and worldview shift that the model helps to cultivate. It illustrates the degree to which different human and ecological systems are thriving or not, and by working with it, forces one to see the interconnectedness of each of these systems—both human and environment—and how a holistic approach is the only plausible way to find long-term solutions and eliminate externalities.

Additionally, because it allows us to hone in on specific issues, it helps us stay focused on the task at hand, one step at a time, becoming a form of mindfulness practice. Over time, one begins to focus on just planting the seeds—less thinking about what will flower, and more about tending to the conditions for that which will flower.

This long-term tending—intentionally caring for something over time—is a necessary ingredient to our collective mindset and stance if we are to align expectations and take the necessary approaches to do design holding a more comprehensive framework.

At essence, we see thriving as a process…as desired conditions shift, the behaviors and ways of living need to shift to remain in that sweet spot/Goldilocks zone. The Doughnut helps us navigate those changing conditions.

The third distinction is the communities around the world using this model in a multitude of ways, and their willingness to share and mentor others along the way. The community of practice is one of the best I have come across over the past two decades in terms of diversity of content and engagement. None of us can do this on our own. Knowing we have a supportive community of practitioners provides us with peace of mind and allows us to focus forward to co-design an Elevated Denver.

In summary, we like it because it paints a simple picture that lets all engaged focus in resonance. The process of using the model and taking action elicits a mindset shift to a longer-term, more systemic view where interconnectedness and the relationships between people, organizations, neighborhoods and the larger ecosystems in which they reside is what leads the action steps. And there is already a community of support with case studies occurring all over the world–giving us the necessary resources, collaborators, and guides to do what we want to do, and do it well. Lastly, we like that the content can be specified by the community itself. If we in Denver want to narrow in on particular realms like food, climate, housing and mental health, then those can be the pictures/ metrics used as anchors to track what’s important to us.

If you would like to go deeper into Donut Economics, please take as many minutes as you are willing to invest considering the content or this video:

If you want more videos, consider following these links:

Kate Raworth on Growth(3:26) – this doesn’t specifically talk about the Doughnut but her view on “growth” is so relevant to the mindset required (imo).

How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy – BBC REEL(BBC Reel with Kate) (6:30) – i like this one for the “short video”)

Downscaling the Doughnut to the City (11:20)

And of course, if you really want to learn this, a great place to start is reading the book:

Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut Economics Seven Ways to think like a 21st Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

We pulled Illustrations and quotes from these places, which we’d also recommend visiting:

https://doughnuteconomics.org/ – Main Page

https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools-and-stories – Tools and Stories

Link to original source of Kate Quote “raises key implications…”: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(17)30028-1/fulltext – (see Supplementary Information for an in-depth exploration of the social indicators and boundaries selected for use in Doughnut v2.0)

We look forward to building on this discussion with you. Stay tuned for the next installment which features the City Portrait, another tool that helps us see a community of interest—neighborhood, city, or nation—from the multitude of perspectives that each community holds.

Join the conversation for an Elevated Denver.

Sign up for the email list and stay in the loop with new podcast episodes, events, and inspiration.